If you’ve ever flown in an Airbus A320 or any Airbus aircraft, you may have noticed that the cockpit doesn’t have the large, steering wheel-like yoke seen in many airplanes. Instead, Airbus uses a sidestick—a smaller, joystick-like device that gives pilots precise control over the plane. But what exactly is the Airbus sidestick, and how does it work?

In this blog, we’ll explain how the Airbus sidestick operates, its advantages over traditional control systems, and why it’s a key feature of modern Airbus aircraft like the A320. Whether you’re an aviation enthusiast or just curious about how airplanes are flown, this guide will help you understand the role of the sidestick in controlling the skies.

What is the Airbus Sidestick?

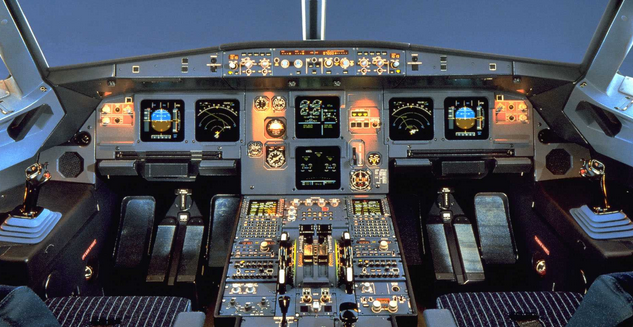

The Airbus sidestick is a primary flight control device used by pilots to steer the aircraft. Unlike the traditional yoke, which is more common in older aircraft and some other manufacturers like Boeing, the sidestick looks more like a gaming joystick and is mounted to the side of the cockpit near each pilot’s seat.

The sidestick replaces the bulky control yoke, offering a sleeker and more ergonomic design. It’s a key part of Airbus’s fly-by-wire system, where pilot inputs are transmitted electronically to the aircraft’s control surfaces instead of using mechanical linkages. This advanced technology allows for smoother and more precise control.

How Does the Airbus Sidestick Work?

In the Airbus A320 and other Airbus aircraft, the sidestick is part of a digital fly-by-wire system. Here’s how it works:

- When a pilot moves the sidestick forward or backward, it controls the aircraft’s pitch—whether the nose points up or down.

- Moving the sidestick side to side controls the plane’s roll, which tilts the aircraft left or right.

Instead of directly controlling the mechanical parts of the plane, like a traditional yoke does, the Airbus sidestick sends electronic signals to the aircraft’s flight control computer. The computer then interprets these signals and moves the control surfaces (like the ailerons, rudder, and elevators) to adjust the plane’s direction and altitude.

The sidestick is highly sensitive, meaning pilots only need to make small movements to control the aircraft. This makes flying less physically demanding, especially during long flights, and gives the pilot more precise control.

Why Does Airbus Use a Sidestick Instead of a Yoke?

Airbus chose the sidestick for several reasons, particularly for its ergonomic advantages and ease of use. Here are some of the key benefits of using a sidestick over a traditional yoke:

- Ergonomics and Comfort: The sidestick’s position on the side of the cockpit allows pilots to rest their arms comfortably while flying. This reduces fatigue, especially during long flights, as pilots don’t need to hold or maneuver a large yoke.

- Clear Cockpit Design: With no large yoke in front of them, pilots have more space in the cockpit and a clearer view of the instrument panel. This makes it easier to monitor flight data and manage other tasks.

- Precision and Sensitivity: The sidestick provides precise control with minimal movement, allowing pilots to make small, accurate adjustments. This is particularly useful during takeoff and landing, where control precision is critical.

- Advanced Technology: As part of the fly-by-wire system, the sidestick works in conjunction with the aircraft’s onboard computers, which assist the pilot by making automatic adjustments and protecting the aircraft from excessive maneuvers.

Sidestick Control in the Airbus A320

The Airbus A320 is one of the most popular commercial aircraft in the world, and its use of the sidestick is a standout feature. Each pilot (captain and first officer) has their own sidestick. When a pilot moves the sidestick, the system translates these inputs into electronic signals that are sent to the flight control computer.

What’s unique about the Airbus A320 sidestick is that it’s not physically linked between the two pilots. In traditional yoke systems, both yokes move together, but in Airbus aircraft, each sidestick operates independently.

To prevent confusion, Airbus has developed a priority logic system:

If both pilots try to control the plane at the same time, the system gives priority to the last input made. A pilot can also press a button to lock out the other sidestick’s inputs, ensuring only one set of controls is active.

This design ensures that there is always clear control during flight and avoids conflicting inputs from the pilots.

The Role of Fly-by-Wire in Sidestick Control

The fly-by-wire system is the technology that makes the sidestick work. In traditional aircraft, pilot inputs are transmitted through mechanical cables and pulleys, which physically move the control surfaces like the rudder, elevators, and ailerons. In the Airbus A320, however, the sidestick doesn’t directly control these surfaces. Instead, it sends signals to a flight control computer, which then adjusts the control surfaces electronically.

This system has several benefits:

- Flight Envelope Protection: The computer system monitors the aircraft’s performance and prevents pilots from making dangerous maneuvers, such as exceeding the aircraft’s safe limits. For example, if the pilot pulls the sidestick too far back, the system will limit the aircraft’s pitch to prevent a stall.

- Automatic Adjustments: The fly-by-wire system makes constant small adjustments to keep the aircraft stable, reducing the workload for pilots and allowing them to focus on higher-level tasks.

In short, fly-by-wire enhances the precision and safety of flying, making the sidestick an intuitive and reliable control tool for pilots.

Sidestick in Action: Takeoff, Cruise, and Landing

The Airbus sidestick is used in all phases of flight, from takeoff to landing:

- Takeoff: During takeoff, the pilot uses the sidestick to lift the aircraft’s nose at the right angle to gain altitude. The precise control of the sidestick helps achieve a smooth, controlled ascent.

- Cruise: While the aircraft is in cruise mode, the autopilot takes over for most of the flight. However, the sidestick remains available for any manual adjustments or to change the flight path.

- Landing: During landing, the sidestick helps the pilot control the descent, particularly in managing the roll and flare (the maneuver of raising the nose just before touchdown). The sidestick’s sensitivity allows for smooth, minor corrections to ensure a safe landing.

Advantages of the Airbus Sidestick

The Airbus sidestick has several advantages that make it a preferred control method for pilots, particularly in modern commercial aviation:

- Ease of Use: Pilots can make small, precise movements with minimal effort, reducing the physical strain of flying.

- Enhanced Safety: The fly-by-wire system, combined with the sidestick, ensures that the aircraft stays within safe operating limits, protecting it from excessive maneuvers.

- Improved Comfort: The sidestick’s position on the side of the cockpit frees up space, giving pilots more room and a clearer view of the instruments.

- Modern Technology: The sidestick is a key feature in the Airbus A320’s modern flight control system, enabling a smoother, more intuitive flying experience for pilots.

Conclusion: The Airbus Sidestick – Precision and Modern Control

The Airbus sidestick is a revolutionary flight control device that has transformed how pilots manage aircraft like the Airbus A320. By combining fly-by-wire technology with ergonomic design, the sidestick allows for more precise, efficient, and safer control compared to traditional yokes.

While it may take some getting used to, the sidestick’s benefits—such as ease of use, improved safety, and reduced pilot fatigue—make it a preferred feature for modern aviation. As Airbus continues to innovate, the sidestick remains a key component in their approach to more advanced and user-friendly flight control systems.